You’ve undoubtedly heard about the plan to ban the sale of new fossil-fuel vehicles by 2030. This won’t affect existing diesel or petrol vehicles, and with more than 38 million on UK roads, the fuel industry is not going to want to rip out the pumps any time soon.

Equally, with only 245,000 all-electric vehicles (EVs) on the road today and some 42,000 charge points (with just 7000 added in 2020), nine years seems a bit optimistic.

But change is coming and with more cities adopting low or ultra-low emission zones, urban centres across the UK and Europe are rapidly becoming less friendly to fossil-fuel vehicles.

Currently, EVs can enter low-emission zones without being charged. To promote the shift to electric, the government might either increase the cost of VED or fuel duty. If there is a big move to EV use in the next few years, it’s clear the fuel duty deficit would fall elsewhere on drivers. One thing is certain – taxes will rise.

The green question

So are EVs actually really that green? They all sport zero-emission claims, but the energy used in their creation, recharging and end-of-life disposal has to be taken into account.

Some EVs are built in carbon-neutral factories, others are not. Some reports suggest they’re more energy-intensive to build than a fossil-fuel car, while the lifespan of the batteries can be as little as eight to 10 years and their lithium cells need careful handling to recycle.

How environmentally friendly the recharging process is depends on the weather and the time of day. Most EVs are recharged overnight, when the grid isn’t reaching any solar charge, and if there’s little wind, the turbines won’t be generating much. So your recharging energy could be coming from coal, gas, nuclear or a variety of biomass power sources, depending on what the national grid is generating.

Even on sunny, windy days, not all of the power in the grid will be green – fossil-fuel plants could be running to help smooth out power in the grid to a stable 50Hz supply. Wind turbines do not produce a steady enough output, from 10-100Hz, so the rest of the grid is used to balance this.

As well as the energy used in an EV’s creation and recharging, you need to consider how many miles you do. The higher your annual mileage, the greener an EV becomes, but motorhomes tend to do low mileages – under 5000 is typical – so the energy involved in creating the EV might never be offset in use. Ideally, fossil-fuel cars and EVs would come with a whole-life CO² rating, based on a couple of annual mileages.

Types of EV

The motor industry loves a good acronym:

- EV (electric vehicle, the generic term)

- BEV (battery electric vehicle, same as EV)

- PHEV (plug-in hybrid electric vehicle)

- HEV (hybrid electric vehicle)

- MHEV (mild hybrid electric vehicle)

Hybrids also have a petrol engine to recharge the battery and extend the range. The latest EV hybrids are permanently powered by an electric motor, with the petrol generator only kicking in when needed. The key point is that after 2030, the only fossil-fuel vehicles to be sold new will be PHEVs, and this will only be until 2035.

Where to charge

The most logical, cheapest place to charge your EV is at home. If you plug into a regular three-pin domestic socket, it will take 14-24 hours to fully recharge your vehicle. Typically, slow-charging an EV takes around 10A, or 2300W per hour.

As most motorhomes are second vehicles, or might not be fully flat when they return home, this could work for some people. But if you want to recharge your ‘van faster, you will need to fit a rapid-charging point at home.

Capacity depends on your location relative to the national grid – city homes have more capacity than those in villages. A 7kW model is the most common size (tripling recharging speeds), with some homes supporting up to 22kW. Chargers can cost around £1000, but government grants of up to £500 are available.

When it comes to recharging away from home, you’d think it would be a common system – like three-pin plugs in our houses, or blue CEE plugs on campsite hook-ups – but the EV industry has added needless complexity by not doing this.

There are four common rapid-charging connectors (CHAdeMO (50kW), CCS (50-330kW), Type 2 (43kW) and Tesla Type 2 (150kW). Different EVs use different systems, but you can check your area, for example on zap-map.com.

You might think campsite hook-up bollards make electric motorhomes a great idea, but it’s not that simple. Rapidly recharging an EV takes more energy than some bollards can provide and some sites – such as The Camping & Caravanning Club’s – don’t allow you to plug directly into the hook-up point. You could slow-charge your ‘van from one of your motorhome’s internal sockets, but this is at the discretion of the site manager.

Even if the campsite will allow you to recharge your EV, it might not leave you with enough spare capacity to run many (or any) of your habitation devices. In time, sites might invest in EV charging points, but this network is still in its infancy.

Tesla rechargers are free to use and all have the same plug system and the cable tethered to the charger (no need to cart bulky cables). Sadly, it doesn’t make vans yet (come on Elon!).

Electric vans currently available

All manufacturers are developing electric vans, but current models in the medium sector include the Nissan e-NV200, Peugeot Partner Electric/Citroën ë-Berlingo, Ford Transit Custom PHEV, LEVC VN5 (electric with petrol range extender), Maxus e Deliver 3, Mercedes eVito, Volkswagen ABT e-Transporter and Citroën ë-Dispatch/Peugeot e-Expert/Vauxhall Vivaro-e.

The ABT Transporter could be the riskiest to justify, with an 82-mile range and prices from £42,000. The Vivaro-e might prove more popular, thanks to a range of up to 205 miles and prices (143-mile, 50kWh battery pack model) starting at £29,000 including a £6000 plug-in grant.

In the larger van sector, there’s the Citroën ë-Relay/Peugeot e-Boxer/Fiat e-Ducato, Maxus EV80, Renault Master ZE, Mercedes eSprinter and VW e-Crafter. The e-Crafter uses the Golf’s 35kW electric drivetrain, so is limited by its 107-mile range, and with prices starting at £63,000 will mainly be used by parcel delivery firms.

The eagerly anticipated e-Ducato has launched with prices from £59,699 (including VAT and the government grant) for the 47kWh battery, 113-mile range model. The long-range battery pack (79kWh, 230 miles) adds £15,000. Given you can buy a new unconverted 180bhp diesel Ducato 35 Maxi LWB high-roof from as little as £24,000, it would be hard to justify the cost savings in fuel.

There are government grants for electric vans, at 35% of the purchase price, up to a maximum £3000 for small vans (for example, the Nissan e-NV200) and £6000 for larger ones.

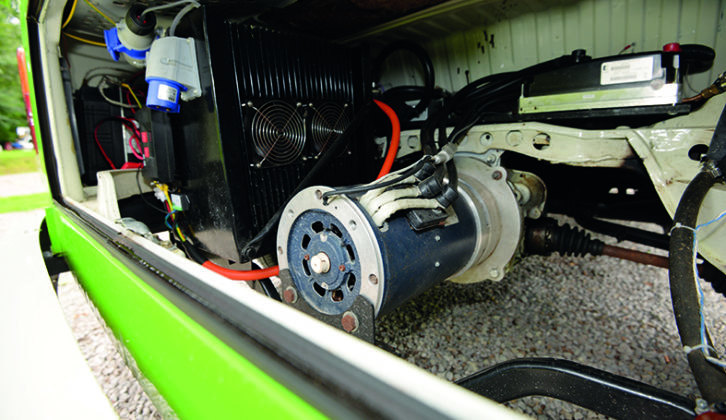

Electric conversions

Many motorcaravanners who are attached to their current vehicle might toy with the idea of having it converted to electric. There are several firms around the UK that do this, but it’s not cheap, with a basic conversion starting at about £20,000. Adding more batteries for a longer range, or more powerful motors for extra speed, will add to the price. At current diesel prices – assuming 30mpg – that’s the equivalent of 93,000 miles of fuel. So you won’t be doing it for the cost savings.

But for certain vehicles, it can make sense. For example, a while back I drove a 1970s VW Transporter converted from a petrol air-cooled motor to electric by eDub Trips. The battery bank had been cleverly hidden under the rock’n’roll bed so the interior was as practical as any other VW campers. What was much better was the performance – far better than the petrol engine and, apart from a slight whine from the motor, significantly quieter and more refined.

The good stuff with an EV

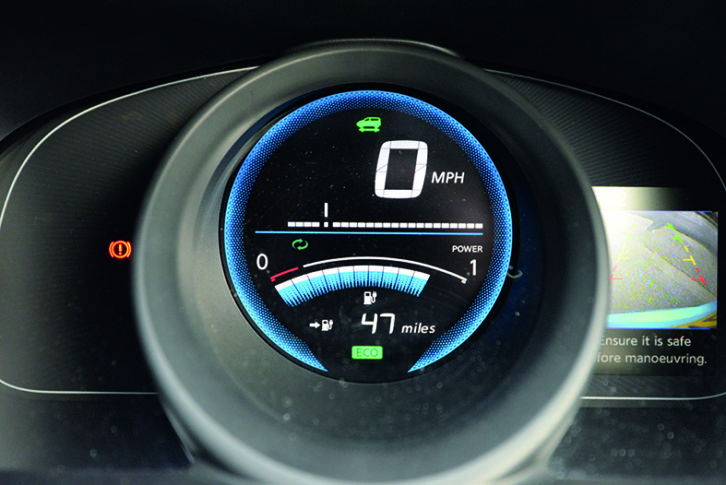

One of the best things about driving an EV is the refinement. I’ve driven an identical campervan – by Hillside Leisure – based on the diesel Nissan NV200 and the all-electric e-NV200. The diesel isn’t the best to drive, especially partnered with rather course suspension.

By comparison, the silent, smooth, effortless e-NV200 – fitted with a similar drivetrain to the Nissan Leaf – was a revelation.

Instant acceleration, no gears and no clutch, it’s a doddle to drive and, thanks to underfloor batteries, living space is uncompromised. As a bonus, the lower centre of gravity caused by the battery pack makes the ride comfort over uneven surfaces far better. If you forget range and the purchase cost, the e-NV200 is clearly better.

One of the very best medium vans that I’ve driven has to be the rather quirky LEVC (London Electric Vehicle Company) VN5.

The firm specialises in taxis and has recently developed the VN5 van version, currently being evaluated by Wellhouse. I tested an unconverted model and was very impressed. It’s always driven by the electric motor (offering up to 61 miles), with a petrol range extender kicking in when needed (for a maximum range of over 300 miles). Fully automatic and silky-smooth to drive, the electric motor gives it a real turn of speed, and inevitably involve fossil fuels and environmental costs. However, these vehicles should last a long time – they have fewer moving parts – and the batteries can be recycled.

Possible cost savings

Most people will save money by recharging their EV at home, if they can, with a typical 60kWh EV battery (giving around a 200-mile range) costing under a tenner to recharge fully.

To give you an idea of cost, a Nissan e-NV200 with a 40kWh battery would cost about £6.12 to recharge from flat overnight. It’s estimated that an EV will add £400-£800 a year to your electricity bill. If you do a lot of miles, this can be a large saving compared to a diesel van.

Public charging points, such as those you’ll find at supermarkets, are often free to use while you’re shopping, so it’s worth taking advantage of them.

If you do more mileage away from home, you’ll need to use a fast charger somewhere on the grid. These are either pay-as-you-go or a subscription. Charging away from home can be considerably more costly – home charging costs 7-20p per kWh – depending on your tariff and where you live. Fast chargers can cost 25-40p per kWh. Some firms charge a one-off registration fee to use their network (about £20), while others add an admin fee per charge (from 50p to £3.50).

There are some free charging stations, but competition for these can be time-consuming if no connections are free when you stop.

Some car parks limit the time of stay, too, and EV-owning friends have complained about getting automatic fines sent in the post if they had to wait for a charger to become free.

If you factor in the extra cost of charging away from home, running an EV might not save a great deal of money, and few will save the extra costs of purchase compared to a fossil-fuel vehicle.

Range anxiety

A lot of ‘range anxiety’ comes down to planning your journeys. So if you’re an organised person who plans holiday time like a military operation, you’ll have little difficulty adapting to an EV.

Most EVs have a range of 150-250 miles. Problems arise if there are no well-placed charging points on your route, or you live in an area where population density is low. You need to allow for the recharging time – motorway rapid-charging for 30 minutes typically adds around 100 miles to the range.

Some people have been known to pack a petrol generator in the back of their vehicle for emergency use! In reality, this would take hours to recharge the vehicle, so it’s best avoided.

Hydrogen and alternatives

At present, there are only 11 hydrogen refilling stations in the UK, grouped around London. Ironically, most produce hydrogen by processing natural gas (yes, a fossil fuel). In time, it’s hoped hydrogen will be produced far more sustainably by issuing the excess power from wind turbines to store it. With the promise of ranges similar to fossil-fuel vehicles and rapid refuelling, hydrogen might dominate some time in the future.

Research into synthetic fuels aims to produce lower-emission sustainable products. Porsche, for example, is working on methanol processed into a synthetic hydrocarbon, petrol or diesel. Making synthetic fuel captures CO² so although it produces emissions – while being a lot cleaner than fossil fuels – that capture makes it carbon-neutral.

The verdict on EVs

If you like to update your motorhome every three or four years, by 2030 you’re only going to have the option of electric, plug-in hybrid or hydrogen. This narrows to electric and hydrogen by 2035.

If you plan trips with military precision, an EV might work, but if you enjoy the freedom of being able to travel without mileage restrictions or being tethered to the charging network, a fossil-fuel vehicle might still be a better choice.

Equally, which vehicle is most environmentally friendly depends entirely on how you use it – just because the tailpipe doesn’t produce emissions, that doesn’t make an EV emission-free.

Electric positives

Electric negatives

|

If you’re on the hunt for a new motorhome, be sure to check our our buying guides, where we round-up the best vans from the biggest manufacturers. For instance, we take a look at the best motorhome for full time living and the best motorhome under 7m, sharing our pick of the bunch, as well as the overall winner in each category at the Practical Motorhome Awards 2022.

You can also find out more about the different brands out there by reading our guide to the best motorhome manufacturers.

If you’re looking for somewhere to head to on your next tour instead, we’ve picked out the best motorhome sites, with locations from all over the country.

If you liked this… READ THESE:

Spotlight on Leisure Batteries

Best motorhome bike rack for 2022

How to upgrade your lights to LED

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, why not get the latest news, reviews and features delivered direct to your door or inbox every month. Take advantage of our brilliant Practical Motorhome magazine SUBSCRIBERS’ OFFER and SIGN UP TO OUR NEWSLETTER for regular weekly updates on all things motorhome related.

Future Publishing Limited, the publisher of practicalcaravan.com / practicalmotorhome.com, provides the information in this article in good faith and makes no representation as to its completeness or accuracy. Individuals carrying out the instructions do so at their own risk and must exercise their independent judgement in determining the appropriateness of the advice to their circumstances. Individuals should take appropriate safety precautions and be aware of the risk of electrocution when dealing with electrical products. To the fullest extent permitted by law, neither Future nor its employees or agents shall have any liability in connection with the use of this information. You should check that any van warranty will not be affected before proceeding with DIY projects.

If you like to update your motorhome every three or four years, by 2030 you're only going to have the option of electric, plug-in hybrid or hydrogen