Back in the early 1900s, the idea of a motorised caravan was first mooted, along with some bizarre designs. Using the principle of coachbuilt bodies, by 1919, the Eccles Motorised Transport Company had begun to produce these on a commercial scale.

By the end of the 1920s, however, the car-pulled caravan took the lead and the motorhome rather faded away. Only a few examples were built and, after WWII, the idea seemed finished.

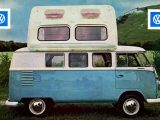

But fast-forward to the early 1950s and the birth of the commercial pressed steel van – and especially the VW Microbus – gave a kickstart to the campervan market.

In 1952, German caravan maker Westfalia spotted the potential. Using the VW, the company started selling a kit conversion for Microbus owners.

Known as the Camping Box, the side-windowed VW Transporter could be converted for basic camping, but the kit could be easily removed if the vehicle was sold. The VW was seen as ideal to convert for accommodation. Soon, new companies were converting it, with a higher spec. But it was costly and VW expected certain standards of quality, too.

Enter the Dormobile

In 1956, one of the most famous names in camper vans, Dormobile, made its debut. Using what was basically an estate car/van, the standard Ten base was designed for sleeping only. It was seen as a new, free and easy way of getting about and exploring off the beaten track. In addition, the VW Microbus was still being used by many UK manufacturers in the early 1960s.

However, the launch of Bedford’s CA van in 1952 gave the opportunity for a convertor such as Dormobile to add accommodation, with a kitchen and seating that converted into beds.

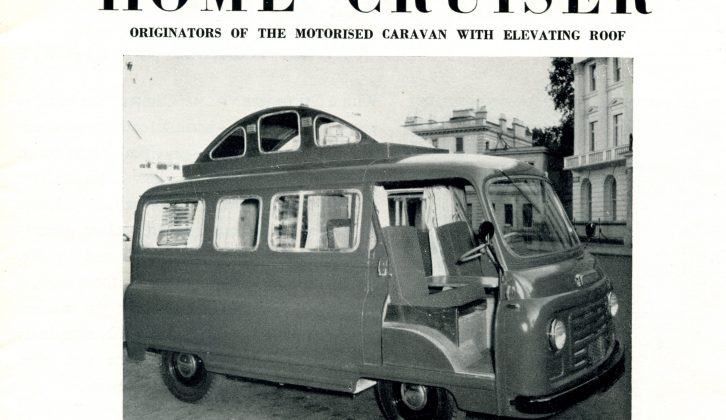

This was also the start of the famous Dormobile extending roof, where two extra berths could be added.

The Bedford CA was taken up by other new convertors, such as Kenex, based in Kent not far from Dormobile, and these camper vans were smartly finished and well designed. Dormobile eventually bought out the company, dropping the Kenex name by 1962.

Other makers sprang up, such as Pitt Conversions and Calthorpe. Different extending roofs were designed, with straight lift-ups made from glass fibre or aluminium with canvas side fillers.

Next came the high-top, with a glass fibre moulded roof section added onto the van after removing the old roof.

Nomad Convertors, based in Bolton, Lancashire, patented a crank wind-up raising-roof – which didn’t always work very well!

Into the 1960s

Later in 1957, the Ford Thames 400E commercial van was released, ushering in a new era in campervan design. The Thames was the answer to the CA and convertors were particularly attracted to the 1.5-litre petrol engine.

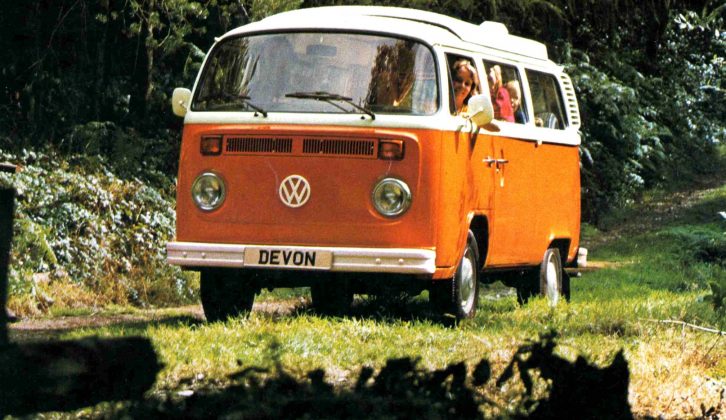

Morris brought out the J4, which became the first choice for many convertors. The 1960s heralded the arrival of many more convertors, such as Devon, Auto-Sleepers, Richard Holdsworth, Airborne, Leisuredrive and Canterbury, among others.

By now, the campervan idea had really begun to take hold and with other commercial vans, such as the Austin and the Commer, and uprated versions, it spread even further.

In the late 1950s, if you owned a campervan, it was still considered a commercial van, so restrictions were imposed, including speed limits.

Peter Pitt of Pitt Conversions decided to protest about this, arguing that the campervan was in keeping with private cars. Pitt’s campaign was so persistent that a law was eventually passed to exclude campers from the category of commercial vans. So legally, the camper was now on a par with a private car.

This new status gave the campervan broader appeal, and firms such as Dormobile had to move to a larger factory. Using VW’s Kombi and Microbus, the Dormobile name became well known in the industry.

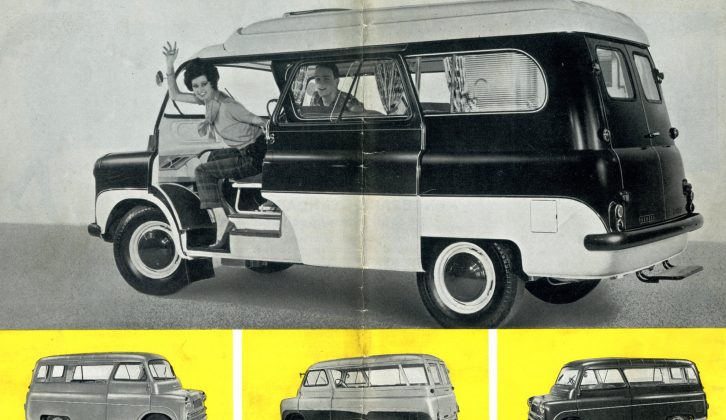

The expanding market produced better designs, and all types of vehicle were now looked at by convertors.

Wild camping

One of the many more unusual vehicles to be seen then was the Land Rover long-wheelbase. Known as the Carawagon, this conversion could sleep up to four, yet was compact inside. Its design meant owners could tour even further off the beaten track, and wild camping began to grow in popularity.

Dormobile jumped on the Land Rover bandwagon, bringing its version onto the market not long after. Later on, Carawagon also built on the Range Rover, but sales of both were limited.

The campervan industry had mainly developed as small concerns, with most selling directly to the public and some offering bespoke layouts. The flip side of this coin was the reappearance of DIY kits. UK makers were offering to kit out older vehicles for buyers on a more limited budget.

In 1969, the Manchester Motor Caravan Company began converting vans to campervans. By the 1980s, this father-and-son business had expanded and was now known as Leisuredrive. Using the VW T3, it gained a reputation for design and quality.

Small firms were making elevating and lift-up roofs for convertors and DIY. Side tents that didn’t need the support of the camper were available from £28. Whale hand-pumped water pumps were being fitted in campervan kitchen units and in some, a drinks cabinet was added.

New dealerships

Campervans were now participating in endurance races, such as a Dormobile that made a 1821-mile round trip from Keighley, West Yorkshire, to Land’s End, then John O-Groats, and back to Keighley,, in 1969.

By now, campervan dealerships were being established, although a few car showrooms also took on campervans.

With the advent of more vans being launched, convertors were spoilt for choice. Then the Ford Thames 400E was dropped, and within weeks of the new Ford Transit being launched, firms such as Dormobile began converting the Transit, with great success. With more space and a modern cab, the Transit was ideal for conversion.

Canterbury Campervans saw the Transit’s potential, with a raising-roof design that sold well; while Dormobile also found a good design, making the Transit one of their top-sellers.

By 1963, Sprite Caravans had merged with Bluebird Caravans, which also made campervans. Known as Caravan International Motorhomes (CIM), the new firm used the Transit for Sprite motorhomes and campervans.

The larger Transit Custom offered more load capacity, so convertors such as CIM soon added this to their ranges.

At the other end of the market, micro-campervans appeared, such as the Bedford-based Dormobile and Canterbury, built on the Ford Escort estate car. Sun-Tor used several such vehicles to make campervans for couples and solo users.

The 1970s saw manufacturers such as Holdsworth and Auto-Sleepers expand, and Bedford’s new CF van proved to be another popular choice for convertors.

Convertors come and go

Over the years, many convertors have ventured into this successful market, for example with the arrival of the Toyota Hiace.

Dormobile was one of the first firms to use the Toyota, although other convertors soon followed.

The British Leyland Sherpa van was another 1970s vehicle that became popular among many convertors. Auto-Sleepers and Motorhomes International were the first companies to convert this to a campervan.

Throughout the 1970s, campervans proved as popular as ever, and a new van from Fiat, powered by an 850 engine, meant that Motor Caravan Conversions, among others, had a success on its hands.

Even though it was small, the Fiat had a kitchen and so on, and was also available with extending side tents.

A dip in sales

Campervans were a good alternative to the coachbuilt, especially for ease of use and parking up. But in 1973, with the introduction of VAT and the advent of the oil crisis, camper sales took a hit. Some firms went bust, but the market eventually recovered.

One positive factor was that the Caravan Club had added motorhomes to its remit in 1967, broadening its membership and helping to popularise ‘van ownership and boost sales.

CIM changed its name to Autohomes, which folded in 1982 when parent company Ci went out of business.

The late 1970s and early 1980s proved tough for the whole sector as the UK economy faltered – even Dormobile became a casualty.

Many of the old names disappeared, but others, such as Holdsworth and Auto-Sleepers, survived, providing reasonably priced campers with quality build. Auto-Sleepers prided itself on quality build and finish.

By the mid-1980s, sales had begun to improve across the market, and the VW T3 proved a popular base vehicle. Autohomes reappeared, introducing new models such as the Komet.

Camper spec also improved, with hot-water systems and mains power. Fitted fridges and full cookers also became the norm.

With new, longer-wheelbase vans appearing on the market – such as the Renault Traffic, Talbot Express and Peugeot – washrooms could be placed at the rear of the camper, allowing for more space in the lounge area.

Mercedes vans have been used by many convertors since the 1970s. There was plenty of choice across the market, which grew rapidly in the late 1980s as more firms started up and caravan manufacturers, such as Elddis and Swift, joined the fray.

Luxury brands

Smaller concerns, such as Nu Venture, started converting Fiat and Citroën vans. Auto-Sleepers focused on the VW Trident and Trooper – these luxury campervans were popular with retired couples who wanted a good spec and finish.

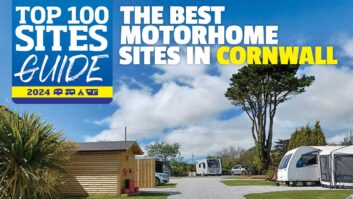

The 2000s saw the arrival of Trigano, La Strada and WildAx, among others, as the market continued to grow. The base vehicles have also become more car-like in terms of drive and spec, with kit such as DAB radio and cruise control now pretty much standard.

The days of the first basic conversions on Bedfords, Fords and Austins may be long gone, but those brands have all played their part in the campervan story, which continues to thrive today.

Campervans enable so many people to take to the road for new adventures, and it should come as no surprise that they are now more popular than ever.

The days of the first basic conversions on Bedfords, Fords and Austins may be long gone, but those brands have all played their part in the campervan story, which continues to thrive today