European On Board Diagnostics (EOBD) is a self-diagnostic system in a vehicle’s electronics.

It first appeared as OBD in the US, where its purpose was to monitor systems controlling exhaust emissions and highlight faults.

The main means of indicating a fault is the malfunction indicator lamp (MIL) on the dashboard, although a problem causing severe emissions might put the vehicle into ‘limp home’ mode as well.

People on forums often ask why their motorhome’s MIL is on, and answers are usually, “Mine did that and it was X, Y or Z” – but that’s meaningless.

So let’s tackle this important issue.

Don’t ignore it!

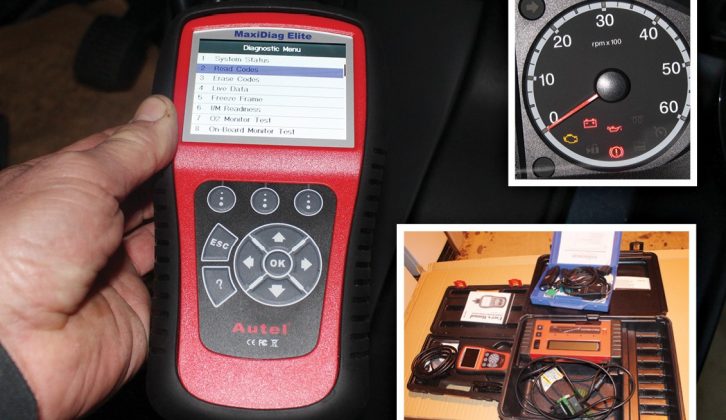

The only way to establish what has caused the MIL to light up is to scan the EOBD system with a scanner, then use the answers to aid a diagnostic procedure.

Many people seem to think that, because the EOBD’s primary function is to monitor emissions control systems, a lit MIL can simply be ignored.

This is foolhardy in the extreme, or what we in the motor trade call the Dirty Harry question: “How lucky do you feel, punk?”

The MIL can be lit for a number of reasons. On a diesel engine, it could be triggered by anything from a dirty air filter to a jumped timing belt or chain, and many more in between.

Most problems will not cause further damage in the short term, but many will result in issues at some point.

One certainty is that faulty components never heal and get better.

Take the dirty air filter for example – in the short term, this is not going to cause major damage, but if left for an extended period, it might cause overfuelling.

That can in turn cause premature failure of the exhaust catalytic converter or even the DPF (if fitted) – both are costly items to fix or replace.

Fault codes are just a first step

So, should we all rush out now and buy a code reader? Most definitely not!

Reading a fault code is just the first step in diagnosing what the issue might be, and this needs to be followed by a logical, careful process of fault finding and component testing on your motorhome.

For example, a heavily clogged air filter could throw up a fault code for excessive EGR flow.

This would lead one to suspect the EGR valve, because we all know how unreliable they are, don’t we?

The reason the fault code shows up as excess EGR flow is the lack of mass air flow being measured in the intake system.

In some vehicles, the EOBD system assumes low air flow to be caused by excess EGR flow – but all it needs is a new air filter.

Modern vehicles, especially diesels, are littered with sensors: air flow, pressure and temperature, crank position, crankshaft speed, camshaft position, knock sensors, coolant and exhaust temperatures, relative exhaust pressures before and after DPF, and oxygen sensors before and after the catalytic converter, to name but a few.

Some engines even have pressure sensors built into the combustion chambers.

Any one of these sensors giving readings outside their normal parameters will almost certainly light up the MIL, but the fault code might not indicate where the fault actually lies.

A solution isn’t always obvious

On some diesel engines, for example, a failed camshaft sensor will cause a non-start situation.

However, if you turn off the ignition, then immediately try to start the engine, it will start and run, albeit badly.

What is happening is this: on the first start attempt, the ECU doesn’t know which cylinder is on the compression stroke because there is no cam position signal.

If you turn it off then immediately try to start, the ECU will switch to batch firing the injectors.

In other words, it will fire cylinders one and four, then two and three, in paired batches, to start the engine and allow you to reach somewhere safe/a place of repair/home.

The engine will run poorly, produce a fair bit of smoke from the exhaust and lack power, but it will allow you to move the vehicle.

If you continued to use the vehicle in this state, it would soon clog the exhaust (DPF if fitted) with soot; the cat (if fitted) would very quickly be wrecked; the turbo could perhaps even be damaged; plus, it would use fuel at an alarming rate.

Depending on the make of your motorhome’s base vehicle, this might throw up a fault code for a cam position sensor, a cam/crank correlation error, low or high exhaust temperature, or low boost pressure.

Only part of the story

Sometimes the fault code points directly at the faulty component, but not always.

A code reader can be helpful if you know what to do with the information it gives you.

At the very least, you can clear the fault code to see if it was caused by a short-term problem.

But it won’t tell you what to do to fix the issue on your ’van.

A keen motorcaravanner, Practical Motorhome’s technical expert Diamond Dave runs his own leisure vehicle workshop. Find out more at Dave Newell Leisure Vehicle Services.

Sometimes the fault code points directly at the faulty component, but not always