Just about every commercially available motorhome nowadays will have at least one leisure battery on board to power the lights, water pump and so on.

But a battery is neither use nor ornament if you have no way to recharge it.

There are three main types of charging system in regular use: mains via the hook-up system, alternator from the engine while driving, and renewable sources.

Renewable energy sources aren’t quite as common as the first two types, but are a popular retrofit option.

Here, we take a look at the differences, and some of the various systems available.

Battery chargers explained

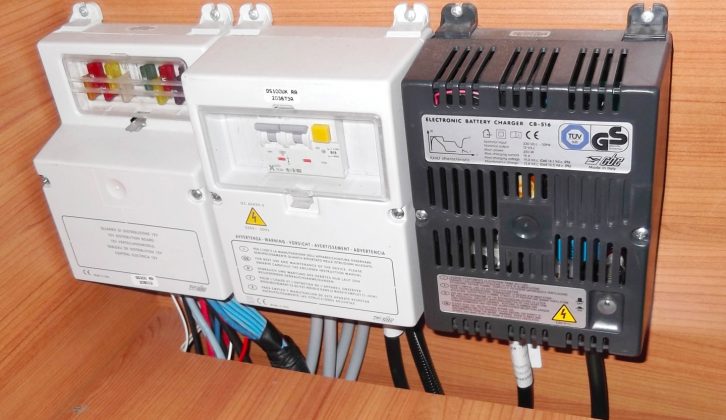

Mains charging of the leisure battery – and sometimes the engine battery, too – is a common system in most motorhomes, but there are several types of charger available.

The simplest is a very basic unit that will give a fixed voltage output, usually of around 13.8 volts. The current (measured in amps) will vary according to the load on the system and the battery’s state of charge.

These basic chargers are rarely used in motorhomes these days, because – for not a lot more money – you can get a multi-stage charger that will extend the life of your batteries no end.

A multi-stage charger will provide charge to the battery at different voltages and currents depending on its state of charge.

What’s a multi-stage charger?

A typical three-stage unit will start with what is called a ‘bulk charge’ mode: this gives a constant maximum voltage and maximum current to recharge the battery quickly. This stage will normally take the battery to around 80% full.

‘Absorption’ is typically the second stage: this will usually give a constant voltage, but with a gradually reducing current to bring the battery up to near-full charge.

The final stage will be ‘float charge’: this stage will typically give a reduced voltage (around 13.2 for a 12-volt battery) and a low current to maintain the battery in a high state of charge.

There are chargers available that do further stages: some of the CTEK range, for example, claim up to eight different stages, some of which are testing the battery condition and the state of charge.

A three-stage charger is the minimum that I would contemplate using in order to maintain my batteries at an optimum level.

The types of charge available

Charging from the engine alternator is often referred to as ‘split charge’.

In its simplest form it uses a straightforward relay to connect the leisure battery and engine battery once the engine is running. It works to some extent, but it does have its limitations.

The biggest problem with simple split charging is that, as the battery voltage increases, the current provided by the alternator will reduce.

This means that it will take a long time to recharge a depleted leisure battery – probably more than a typical journey would last.

Battery-to-battery

The best solution is to use a battery-to-battery charger (B2B). These devices electronically replicate the multi-stage charging regimes, but use the alternator as the power source.

Unless you are driving for seriously extended periods, it’s unlikely that a B2B will fully recharge a heavily depleted battery, but it will get more energy back into it than a simple-split charge system would.

Such systems are ideal for those who do a lot of off-grid camping, but who only stay in one place for a day or two.

Harnessing the power of nature

Renewable energy sources are solar and wind power. Solar is a very popular option these days – wind-powered generators, meanwhile, are available, but aren’t as commonplace.

Solar panels come in two main types: monocrystalline and polycrystalline. The major difference between the two varieties is size – a poly panel will typically be about 5% larger than a mono for the same quoted output.

The other options for panels are rigid or semi-flexible. To my mind, the only advantage of a flexi panel is that it can be walked on.

As such it’s ideal for boats, where it could be glued onto the deck, but there is little advantage in a motorhome. Rigid panels tend to be more reliable, too.

Solar panels are rated in maximum wattage, and vary from about 20 watts up to around 150.

A 100W panel could in theory produce around eight amps, but the reality is that it will rarely get that high – five or six might be closer to the truth.

Regulating solar and wind power

Any solar- or wind-powered generator will need a regulator to control the charge going into the battery.

A typical solar panel in full sun will produce around 22 volts, which is obviously too high for a 12-volt battery – the regulator’s job is therefore to reduce this to a safe charging level. There are many different solar regulators available.

At the cheapest end of the scale they will replicate the simple split charge or basic fixed voltage charging systems previously mentioned.

At the dearest end they’ll provide multi-stage charging regimes.

PWM and MPPT explained

The two main types of regulator are PWM and MPPT. PWM stands for Pulse Width Modulation, and controls the charging voltage by simply switching it on and off rapidly – the duration of the ‘on pulse’ relative to the ‘off pulse’ will give an average voltage output.

These systems work pretty efficiently, and it is a well-proven technology, but it doesn’t always make the best use of the panels’ output.

MPPT is the newer technology. This system electronically matches the output voltage of the panel to the battery’s requirements.

It is claimed to harvest up to 30% more energy in cold and dull conditions compared with PWM systems. Solar systems are well-suited to off-grid camping, where the ’van will be stationary for more than a couple of days.

A keen motorcaravanner, Practical Motorhome’s technical expert Diamond Dave runs his own leisure vehicle workshop. Find out more at Dave Newell Leisure Vehicle Services.

A three-stage charger is the minimum that I would contemplate using in order to maintain my batteries at an optimum level